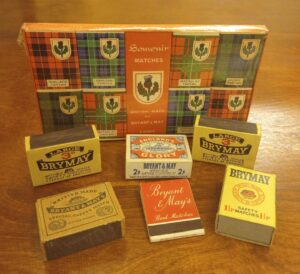

Bryant & May was a British company founded in 1843 to make matches. Its original match factory closed in 1979 while its last match factory closed in 1994.

In the 150 years of her life she has made thousands of different matchboxes, and many of them are in the private collection of the “matchesmuseum”.

In the 150 years of her life she has made thousands of different matchboxes, and many of them are in the private collection of the “matchesmuseum”.

A fascinating element of its history, but also of the development of the labor movement, was the strike that broke out in the summer of 1888, at the end of June-July, in the then well-known Bryant & May industry, which was one of the largest industrial units in Great Britain. It was called the “match girls’ strike” and is considered an iconic moment in the history of the British labor movement.

Photo with young striking workers of the Bryant & May Industry. At the far right we see a little boy who sells matches with his box. Photo from the collections of the UCT Library of the Metropolitan University of London.

Photo with young striking workers of the Bryant & May Industry. At the far right we see a little boy who sells matches with his box. Photo from the collections of the UCT Library of the Metropolitan University of London.

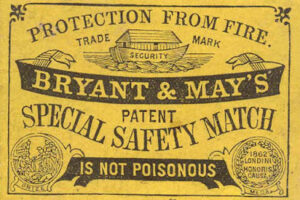

Bryant & May Match Advertising. Bryant & May matches protect against fire. They are safety matches and not poisonous says the advertisement.

Bryant & May Match Advertising. Bryant & May matches protect against fire. They are safety matches and not poisonous says the advertisement.

Aerial photography. The Bryant & May matchmaking industry from above around 1910. It was located in the Bow area of East London. It was Britain’s largest industry and in its heyday employed around 3,000 workers, working and living in miserable conditions.

Aerial photography. The Bryant & May matchmaking industry from above around 1910. It was located in the Bow area of East London. It was Britain’s largest industry and in its heyday employed around 3,000 workers, working and living in miserable conditions.

In the East London suburbs, the poorest sections of London lived in squalid housing. Women and children worked for little money in the industries and workshops in the area. Many children did street work and were malnourished. Of course, they did not go to school.

1889 photograph showing cheap working-class housing on a East London street. The inhabitants are poorly dressed and we see barefoot children.

1889 photograph showing cheap working-class housing on a East London street. The inhabitants are poorly dressed and we see barefoot children.

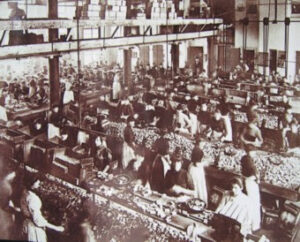

The Bryant & May match factory in 1861-1862. We see women workers.

The Bryant & May match factory in 1861-1862. We see women workers.

In the mid-19th century, two Quakers, Francis May and William Bryant, teamed up to set up a trading company importing and distributing safety matches from Sweden. In 1861 the company expanded and bought in the Bow of East London a huge ruined area where in the past there were workshops for making candles, crinolines and ropes. They renovated the site’s facilities and turned them into a match factory. Their original purpose was to produce high security matches. The cost of these matches, however, was very high and for this reason, the public continued to buy the cheaper traditional matches, despite the fact that they were dangerous. So the Bryant & May factory abandoned the production of expensive safety matches and began making cheaper matches using white phosphorus, which is dangerous to workers’ health.

Female workers at the Bryant & May match factory. 1871. Warder Collection.

Female workers at the Bryant & May match factory. 1871. Warder Collection.

Newspaper lithograph (1905) depicting female workers putting phosphorous matches in boxes. The majority of workers in the match industry were women, mostly young girls but also girls thirteen or thirteen years old.

Newspaper lithograph (1905) depicting female workers putting phosphorous matches in boxes. The majority of workers in the match industry were women, mostly young girls but also girls thirteen or thirteen years old.

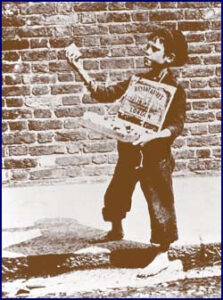

Poor children, girls and boys, were selling matchboxes on the streets of London.

Henry Mayhaw, The Girl Who Sells Matches. 1861-1864. Museum of London.

Henry Mayhaw, The Girl Who Sells Matches. 1861-1864. Museum of London.

Boy selling matches in East London. Late 19th-early 20th c. He is barefoot.

Boy selling matches in East London. Late 19th-early 20th c. He is barefoot.

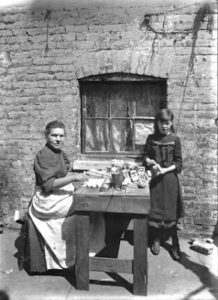

Some poor women worked from home, filling boxes with matches supplied by the Bryant & May industry. They earned little money needed to supplement their meager family income.

Photo showing a woman and a little girl at the table in their yard putting matches in boxes. Around 1900.

Photo showing a woman and a little girl at the table in their yard putting matches in boxes. Around 1900.

Workers at the Bryant & May Match Factory in the late 19th century. Working conditions were very difficult, workers were treated inhumanely and their pay was extremely low. In addition, white phosphorus was very dangerous to the health of workers who often had a type of bone cancer.

Workers at the Bryant & May Match Factory in the late 19th century. Working conditions were very difficult, workers were treated inhumanely and their pay was extremely low. In addition, white phosphorus was very dangerous to the health of workers who often had a type of bone cancer.

The inhumane working and living conditions of matchmakers were made public by radical journalist Annie Besant, who published fiery articles in the social media newspaper “The Link” against the Bryant & May company and in favor of worker protection.

The militant radical journalist and activist Annie Besant (1847-1933). She left her conservative family life (she had two children) with her clerical husband, to devote herself to the struggle for the rights of women and workers. He wrote articles in newspapers and aroused the public with her fiery speeches. She moved to the socialist circles of London, she was a friend of the famous Irish writer Bernard Shaw, of Eleanor Marx (daughter of Karl Marx) and other well-known left-wing politicians and intellectuals of England. She was in favor of the Indian national movement (she traveled to India where she was politically active) and the Irish struggle for national self-determination.

Annie Besant in the 1880s. She was actively involved in the Bryant & May matchmaker strike, organized their struggle, defended their rights and led their committee.

In June 1888, at a meeting of leftists and socialists, Besant overheard left-wing activist Clementina Black talk about women labor and learned about the working conditions and low wages of Bryant & May industry workers. Shocked by what she heard, she went outside the factory and managed to interview some of the workers, who confirmed Black’s information.

Besant learned that the women worked fourteen hours a day for five shillings a week, an amount that was often not paid in full, due to fines imposed by the administration. Fines were imposed if they spoke during working hours, if matches were falling from their hands, if they went to the toilet without permission, if they were late to get to work.

On June 23, 1888, Besant published an article in the left-wing newspaper “The Link”, of which she was the publisher and editor. The article was titled “White Slavery in London” and referred to the working conditions of Bryant & May’s industrial workers. In addition, she talked about the effects that the preparation of matches with white phosphorus had on the health of workers. Their skin turned yellow, their hair fell out, they contracted a bone necrosis disease and eventually died. Although some countries had banned the use of phosphorus for making matches (e.g. Sweden, USA), it was banned in Great Britain in 1910.

The second page of “The Link” newspaper where Besant’s article was published.

Besant’s publications in the newspaper continued in July.

The publication of the article provoked the reaction of the factory management. The workers were forced to sign a statement that Besant’s information was not true. When three workers refused, they were fired from the factory. This was the reason for the mobilization of their colleagues. In early July 1888 a group of 200 workers, mostly young girls, left their jobs in the match factory and went to the newspaper office to ask for Besant’s support. The strike had begun.

Newspaper lithograph depicting workers protesting in the streets of London. Many of the workers who took part in the strike were of Irish descent.

The number of strikers soon increased to 1,400 workers, despite the terrorism perpetrated by the factory management. Threats to relocate the plant to another city or to Norway and the false statements of its founders to the press did not dampen the workers’ militant mindset organized under Besant.

Eventually, the factory management, under pressure from the public, was forced to back down and accept the workers’ demands for better working conditions and the provision of basic health care.

Lithograph from a newspaper of the time. The workers are protesting at the entrance of the factory.

Photo depicting the Committee of Striking Workers with Annie Besant in the center giving a speech.

Three striking workers, members of the Commission. Detail of the same photo. Uneducated and unskilled workers, with no previous experience in the trade union movement, found themselves at the forefront of a strike that shook London for three weeks.

Annie Besant organized the Committee of Striking Workers and directed their struggle. He even managed to lead the members of the Commission to Parliament and to be accepted by Members to whom they made their demands for better working conditions.

Two Bryant & May matchmakers. The industry survived in the same area until the 1970s.

Bryant & May factory workers. Photo from the last years of operation. The name of the company Bryant & May still survives and the usage rights belong to a Swedish company.

The factory today. The buildings have been renovated and converted into modern apartments for those who have the money to live in a historic space and the mood to live daily in the atmosphere of the past with the comforts of mo